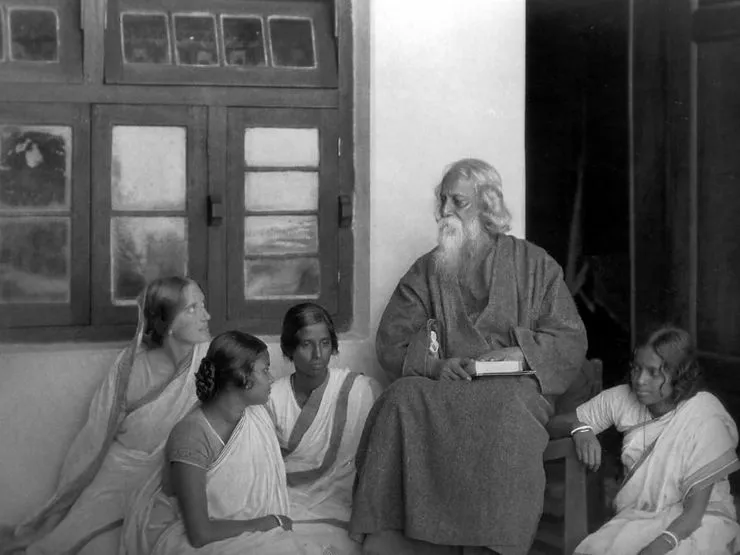

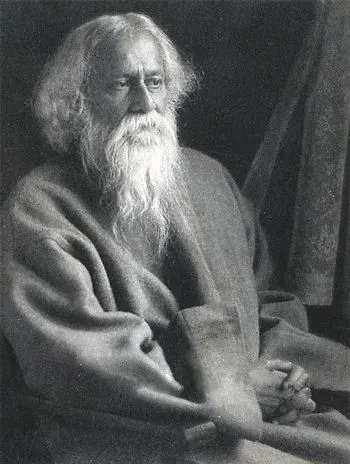

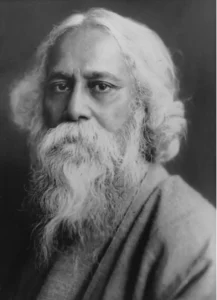

Rabindranath Tagore, often celebrated for his intellectual breadth, was more than a poet or philosopher. His influence spanned literature, painting, social reform, and education. His reflections on nationalism and patriotism stand out for their clarity and continued relevance. Through essays and fiction, Tagore examined these powerful ideas not just as political principles, but as forces that shaped human values and collective behavior.

Tagore’s Perspective on Nationalism

In 1917, Tagore compiled a series of essays under the title Nationalism, offering an in-depth critique of national identity through three key essays: Nationalism in India, Nationalism in the West, and Nationalism in Japan. His interpretation of the nation as a political and economic entity tied together by purpose led him to question the ethical implications of nationalism. He saw the danger in nationalism becoming a mechanism of domination, where the pursuit of material gain overshadowed moral considerations.

Tagore did not reject love for one’s country. His concern centered on the way nationalism could evolve into a self-serving ideology, often aligned with violence, conquest, or exclusion. He observed that prioritizing national pride without grounding it in ethical awareness led to a corrosion of civic responsibility. Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, in his analysis of Tagore’s political thought, points out that Tagore’s views shifted over time. His engagement with the Swadeshi movement during the partition of Bengal marked a phase where his sentiments aligned with the nationalist cause. However, this alignment began to evolve as he saw its limitations.

Nationalism in The Home and the World

Tagore’s novel Ghare Baire (The Home and the World), written during the Swadeshi movement, explores competing visions of nationalism through its protagonists—Nikhil, Bimala, and Sandip. Nikhil stands for ethical leadership and reason. Sandip embodies a charismatic, aggressive form of nationalism. Bimala, caught between their ideologies, reflects the inner conflict faced by many during the struggle for independence.

Through these characters, Tagore exposed the emotional appeal of nationalist rhetoric. Sandip manipulates patriotism for personal influence, showing how easily ideals can be twisted. Nikhil, though less persuasive in speech, remains grounded in principle. Tagore uses their contrast to highlight the need for integrity in public life. In Bimala’s grief, the narrative reveals the personal toll of misplaced political fervor.

Tagore’s Ideological Discourse in Gora

Another of Tagore’s major works, Gora (1910), engages deeply with the evolving debates on national identity. Set in the wake of the Swadeshi movement, Gora presents its title character as someone who equates Indian pride with religious orthodoxy. Binoy, his close companion, represents an alternative path, one rooted in humanism and ethical reasoning.

Through its female characters—Lolita, Sucharita, and Anandamoyi—the novel opens space for critical dialogue on reform and identity. These women, drawn from progressive households, engage the male characters in thoughtful conversation and influence their ideological journeys. Tagore reveals Gora’s origin late in the novel, showing him to be of Irish descent, raised by an Indian woman after his parents died in 1857. This discovery transforms Gora’s understanding of identity. No longer bound by birth or religion, he begins to embrace a broader sense of belonging.

Gora serves as a powerful metaphor for India’s search for national consciousness. Tagore contrasts narrow nationalism with a wider love for the nation grounded in pluralism. He uses Gora’s transformation to critique exclusionary forms of patriotism and to advocate for inclusive citizenship.

Distinguishing Between Nationalism and Patriotism

Ashis Nandy, writing in Nationalism, Genuine and Spurious, draws from Tagore to illustrate the distinction between nationalism and patriotism. According to Nandy, nationalism as an ideology constructs a defensive posture that alienates others. Patriotism, by contrast, emerges as an emotional and cultural connection to place and people. Tagore’s discomfort with nationalism stemmed from its association with power, hierarchy, and control. His understanding of patriotism was rooted in empathy, care, and shared humanity.

Tagore envisioned love for the homeland as a relationship shaped by ethics and compassion. He criticized rigid caste structures and communal divisions, recognizing that the struggle for independence could not succeed without addressing the injustices within Indian society. In Tagore’s view, a true national awakening required moral clarity and social reform.

Tanika Sarkar, reflecting on Tagore’s critique, wrote that his idea of patriotism rested on care—not conquest. It was a commitment to people, culture, and the land itself. Patriotism, for Tagore, demanded the freedom to love without conditions. Without that, no ideology—however noble—was enough.

Conclusion

Tagore’s writings reveal a deep concern for the ways ideologies can shape society. His fiction and essays provide a lasting reminder that national identity must be built on truth and compassion. By distinguishing patriotism from nationalism, Tagore created a space for dialogue—one where justice, freedom, and plurality could coexist.

In today’s world, Tagore’s ideas remain vital. His call to love one’s country while resisting blind allegiance continues to resonate. Through literature and thought, he offers a vision of a nation that values its people more than its power.