The legacy of Tipu Sultan continues to provoke debate and divergent interpretations. For some, he represents a heroic figure of resistance and a symbol of communal harmony—one historian even portrayed him as a protector of Hindu traditions. Others regard him as a sectarian ruler, notorious for coercive practices. These polarized views often fail to reflect the intricate context in which Tipu operated, missing the historical nuance necessary for fair assessment.

A gold coin from the reign of Haider Ali, Tipu’s father, bears witness to the religious plurality of the time. One side depicts Shiva and Parvati, while the reverse carries his initials in Persian script. Tipu’s political vision was shaped by a blend of religious symbolism and statecraft. In 1797, he reached out to the Shah of Afghanistan proposing a joint military campaign under the banner of a ‘holy war.’ The suggested plan was complex—beginning with the dethroning of the Mughal emperor and forging an alliance with Rajput forces, eventually leading to a southern march that included Brahmin and other caste support. Tipu framed the British, the Marathas, and the Nizam as enemies of Mysore and, by extension, enemies of God. His governance model was titled the Khudadad Sarkar, positioning himself as God’s representative.

This rhetorical strategy was not unusual for rulers of that era. Martanda Varma of Travancore, for example, declared his state as ruled by Lord Padmanabha, casting himself as a mere servant. In such political cultures, invoking divine legitimacy was often a method to consolidate authority. For Tipu, aligning religion with politics was a way to sanctify his power, not always a sign of religious fervor.

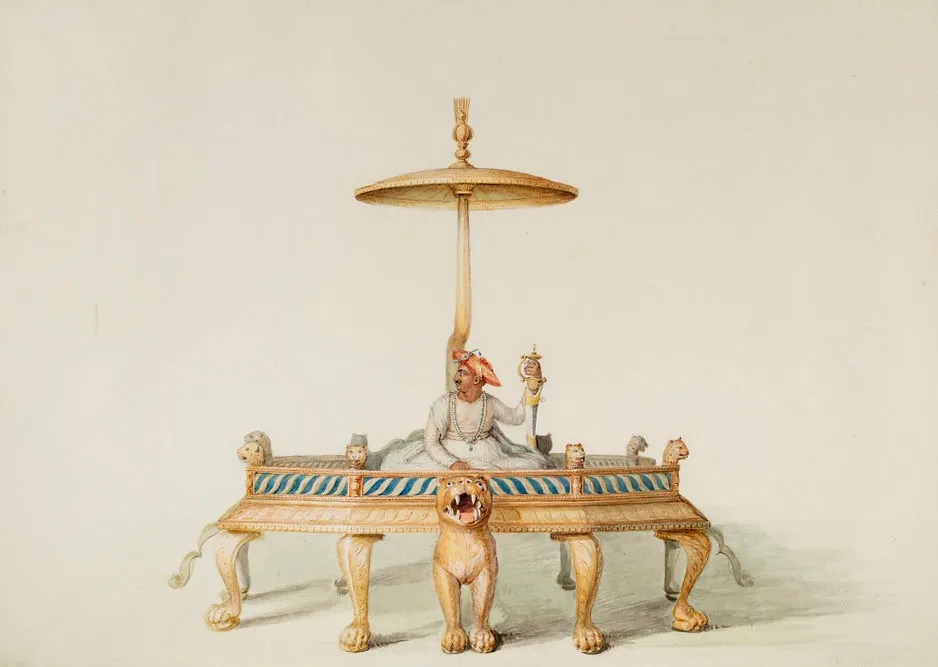

Haider Ali had retained traditional structures, including the symbolic authority of the Wodeyar king. His administration largely mirrored existing Indic governance norms. An East India Company officer once described him as “half-Hindu.” Tipu, however, pursued legitimacy through diverse cultural references. He embraced symbols that resonated across faiths. Kate Brittlebank has highlighted his frequent use of the tiger motif, which evoked Islamic saints, Hindu deities, and regional dynastic traditions. His associations extended to both Hindu monks and Sufi mystics. Depending on the political climate, temples might receive royal support or suffer destruction.

During military campaigns, particularly in Malabar and Tamil regions, Tipu’s forces damaged several temples. At least three major shrines within his territory were demolished. Yet, he extended considerable patronage to others. Temples located in politically significant areas such as Srirangapatna and Bangalore received his support. The Sri Ranganathaswamy and Kote Venkataramana temples stood in close proximity to his palaces, challenging monolithic portrayals of him as an iconoclast. These contradictions suggest a pragmatic approach, where religious actions often served political ends.

Sacred sites located in contested regions frequently became targets. Their destruction undermined the legitimacy of rival rulers and disrupted claims of divine right. Loot, including valuable artifacts, was another incentive. One temple gift from Tipu included a church bell taken from a Christian site in Kerala, indicating the fluid nature of sacred symbols and political spoils.

As ruler of a predominantly Hindu population, Tipu had practical reasons to maintain and protect temples within his dominion. Donations to shrines at Melkote, Nanjangud, Kalale, and Srirangapatna reinforced his authority. Scholar Caleb Simmons has argued that by associating himself with longstanding temples, Tipu was aligning with the legacy of older dynasties. His relationship with the Sringeri Shankaracharya followed this logic. Over the course of his reign, he corresponded with the Jagadguru more than 40 times, referring to the pontiff as essential to the kingdom’s wellbeing.

At the same time, Tipu’s policies reflected a growing desire to project a distinctly Islamic royal image. Persian replaced Kannada in administrative affairs, and cities were renamed—Devanahalli became Yusufabad, and Chitradurga became Farkhyab Hisar. Between 1795 and 1798, evidence shows that non-Muslim merchants were taxed at a higher rate than Muslim traders. In correspondence with a regional Nawab, Tipu claimed to have converted thousands of Kodavas to Islam. While conversions occurred, such statements likely served as rhetorical assertions of power rather than records of systematic religious campaigns.

Tipu’s reign cannot be understood through binary judgments. His religious policies often mirrored the broader political landscape of 18th-century India. The common trope that casts him as uniquely intolerant relies on selective memory. When the Sringeri matha suffered a devastating attack in 1792, it was not Muslim troops who were responsible, but Maratha forces under Parashuram Bhau. That raid resulted in the deaths of several Brahmins, desecration of the Sharada idol, and the molestation of women. Yet, this episode rarely sparks demands for redress, unlike those involving Tipu.

Historical figures are rarely one-dimensional. Tipu appears in murals commissioned by Hindu courtiers, donating sacred lingams to temples and resolving sectarian disputes, even while ordering military actions that involved desecration. He was accused of persecuting Brahmins, but relied on them heavily for administration. His Diwan, Purnaiah, was a Marathi Brahmin.

Rather than attempt to balance virtues against flaws, understanding Tipu requires context. Power in pre-modern South Asia often operated through negotiation, symbolism, and religious sanction. Rulers—whether Muslim or Hindu—frequently combined piety with violence, patronage with persecution. Simplistic classifications obscure this reality.