Shamanism represents the spiritual practices of indigenous cultures worldwide, with shamans serving as intermediaries between the physical and spiritual realms. These figures play a crucial role in addressing various concerns, from health and fertility issues to agricultural success. Many tribal communities in India continue to uphold shamanistic traditions, with each group assigning unique names to their spiritual leaders. Among them, the Santals refer to their shaman as an ojha, while the Kharia community calls theirs a pahan.

Art plays a significant role in these practices, often manifesting in ritualistic wall paintings that depict ancestral beliefs, divine interventions, and mythological narratives.

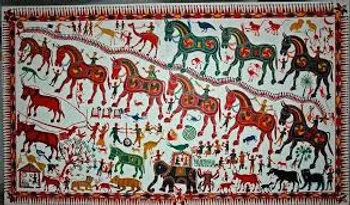

Pithora Paintings of the Rathva Community

The Orissas of Gujarat, residing mainly in the Panchmahals and Baroda districts, continue to practice shamanistic rituals that deeply influence their way of life. Predominantly engaged in agriculture, this community holds a strong belief in ancestral spirits, offering food and symbolic objects to appease those who may have suffered untimely deaths. These spirits, referred to as jiv, are believed to wander restlessly unless proper rituals are performed.

The badvo, or shaman, serves as the spiritual guide responsible for communicating with these ancestral entities. One of the most distinctive features of these rituals is the creation of Pithora paintings, elaborate wall artworks that narrate the wedding procession of Baba Pithoro, the community’s revered deity. These paintings prominently feature horses, a motif also observed in ancient rock shelters within the region. The ritual culminates when the deity, through the badvo in trance, examines and acknowledges every figure depicted in the painting.

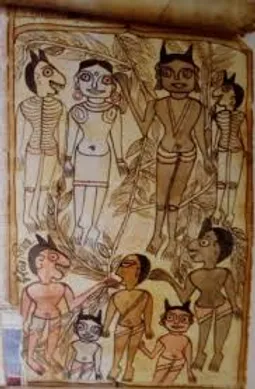

Saura Paintings and Ritual Practices

Among the Sauras of Odisha, shamanistic traditions continue to thrive. Here, the shaman, known as the Kudang, acts as the bridge between the living and the spirit world. Families seek his guidance when they experience hardships, including illnesses and misfortunes. The Kudang first identifies the source of distress by casting rice grains into fire and gauging the pulse of the afflicted. Through drumming and chanting, he enters a trance state, enabling direct communication with the kulba, or ancestral spirit responsible for the ailment.

The culmination of this ritual is the creation of a wall painting, directed by the spirits themselves. Using a twig as a brush and natural pigments, the Kudang decorates the walls of the affected household with figures representing humans, animals, and abstract geometric designs. Known locally as Ekon, these paintings embody symbolic meanings that remain difficult to decipher. Despite the decline of this artistic tradition, its purest form continues to be preserved by the Lanjia Saura community, believed to be among the earliest worshippers of Lord Jagannath.

Jadu Patua and the Art of the Santhals

The Santhals, one of India’s largest tribal communities, inhabit regions across West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, and parts of Bangladesh. Their religious beliefs revolve around polytheism, attributing spiritual significance to natural elements such as forests, hills, and rivers. They believe that ancestral spirits influence their lives, with the ojha serving as the designated healer who communicates with these entities.

A particularly intriguing aspect of Santhal funerary practices is the involvement of Jadu Patuas, or magic painters. These artists play an essential role in death rituals, where they create paraloukik patas, paintings that dictate the offerings required for the deceased’s transition to the spirit world. The Jadu Patua arrives with a collection of stock paintings depicting various human figures. From these, the family selects an image that closely resembles the departed. Initially, the eyes of the figure remain incomplete, symbolizing the soul’s entrapment between the earthly and spiritual realms.

As the ritual progresses, the painter persuades the family that unless the eyes are completed, the spirit will be unable to cross over and may return to haunt them. Once the family consents, the final brushstroke is applied, marking the symbolic release of the soul. This ritual, known as Chokkhudan pata, holds deep cultural significance, reinforcing the Santhal belief in ancestral influence.

The Connection Between Shamanism and Art

Shamanistic traditions and ritualistic art are deeply intertwined in many indigenous cultures across India. These artistic expressions serve as spiritual tools, facilitating communication with the divine and preserving ancestral knowledge. Similar traditions have been documented in various cultures worldwide, including the Aboriginal communities of Australia and the San Bushmen of the Kalahari in Africa.

Despite modernization, these unique practices continue to offer invaluable insights into India’s rich cultural heritage, emphasizing the enduring relationship between spirituality, art, and community identity.

References

- Jyotindra Jain (2010). Painted Myths of Creation: Art and Ritual of an Indian Tribe, Lalit Kala Academy, New Delhi.

- Rudolf Rahmann. Shamanistic and Related Phenomena in Northern and Middle India.