Part 1: Early Life

Motilal Nehru was widely recognized for his sharp intellect, persuasive demeanor, and keen sense of humor, which often lit up courtrooms. However, his personal life was marked by profound sorrow. He endured the tragic loss of his first wife and newborn son during childbirth. Deeply affected by the experience, he resolved never to marry again. Yet, at his mother’s insistence, he eventually agreed to wed Swarup Thussu, a striking young woman known for her hazel eyes and rich chestnut hair.

Swarup came from a relatively recent Kashmiri migrant lineage, in contrast to the Nehru family, who had settled in the plains nearly a century earlier. Her delicate features, likened to ‘Dresden-china perfection,’ and gracefully shaped hands and feet set her apart. As the youngest in her family, she had been indulged by her parents. However, historian B.R. Nanda noted that adapting to her new household was challenging. She had to navigate the expectations of a large extended family, presided over by a formidable mother-in-law known for her fiery temper.

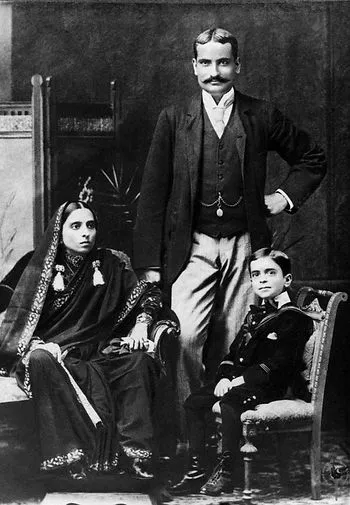

Despite these challenges, Swarup and Motilal formed an elegant couple. Yet, sorrow struck again when their first child, a son, did not survive. This loss was followed by the passing of Motilal’s elder brother, Nandalal, in 1887, leaving him responsible for his widowed sister-in-law and her seven children. While he accepted this duty without hesitation, he longed for a son. Predictions that he would never have one added to his distress. Ironically, just ten months after this forewarning, on November 14, 1889, at 11:30 PM, Swarup gave birth to a son—Jawahar, meaning “precious stone.” With his father’s growing financial success, the boy was raised in luxury, cherished by both parents.

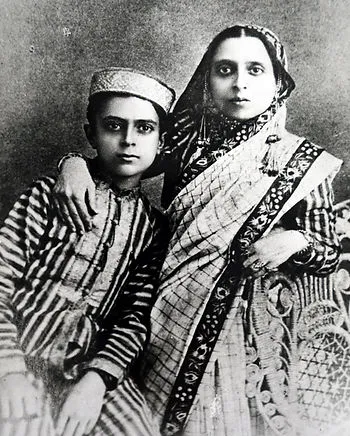

There is limited historical documentation on Swarup Rani, and much of what is known about her comes through accounts of her husband and son. She was deeply protective of her child, driven by superstition to shield him from harm. She discouraged comments about his appearance, intelligence, or health, fearing the “evil eye.” To ensure he never looked too eager at meals, she would serve him a private snack before dinner. A black dot (tikka) was often applied to his forehead as a safeguard against misfortune.

In his autobiography, Jawaharlal Nehru reflected on his parents:

“I admired my father tremendously… My admiration and affection for him remained strong, but so did an underlying fear. With my mother, it was different. There was no fear—I knew she would forgive anything.”

He admitted that her unconditional love allowed him to exert a degree of control over her, and he saw her as his confidante. As he grew, reaching her height, he felt more like an equal to her than a subordinate. When his father disciplined him, it was his mother he turned to for comfort.

Swarup, along with her sister-in-law, immersed young Jawaharlal in Hindu mythology, religious ceremonies, and rituals. She frequently took him to the Ganges for sacred dips and temple visits. The family celebrated Hindu festivals such as Diwali and Holi with great enthusiasm, as well as Eid. However, Naoroz, the Kashmiri New Year, held a special place in their household, marked by new attire and monetary gifts.

Motilal, meanwhile, embraced a more modern lifestyle. He traveled abroad frequently, refused to observe traditional ablutions, and owned a fleet of cars. There were even claims that he sent his linen to be laundered in Paris. Yet, despite his Westernized approach, he never entirely removed religious traditions from the household. Swarup, while accommodating English governesses and Western dining habits, remained deeply devoted to her faith. She maintained a strong connection to religious scriptures, rituals, and frequently visited Benaras and Haridwar. This coexistence of cultural influences defined Anand Bhavan, their family home.

Swarup’s health had been fragile since Jawaharlal’s birth. However, in 1900, eleven years later, she gave birth to a daughter, Sarup Rani, later known as Vijay Lakshmi Pandit. In May 1905, the family embarked on a voyage to London with two objectives—enrolling Jawaharlal in a school and seeking medical treatment for Swarup. Once Jawaharlal was admitted to Harrow, doctors in London recommended a series of treatments at European health resorts. The family visited mineral springs in Cologne and Bad Homburg, yet none yielded the hoped-for improvements.

Her condition worsened, prompting the family’s urgent return to India. Even as Motilal and Jawaharlal engaged in political discussions through letters, Swarup’s health remained a constant concern. She maintained correspondence with her son, writing in colloquial Hindustani, her words brimming with emotion. When illness prevented her from writing, it was the only time she failed to send her weekly letters, in which she often reminded him to wear warm clothing and keep a thick rug on his bed.

Amid these health struggles, a brief moment of joy arrived in November 1905 when another son was born. Motilal, overjoyed, wrote to Jawaharlal:

“The little stranger chose your birthday as the most fitting time to come into this world…”

However, the family’s happiness was fleeting, as the child, Rattan Lal, passed away within a month.

In 1907, on November 4, Swarup gave birth to a second daughter, Krishna, affectionately called Beti. Years later, Krishna would recall:

“I hardly remember a time when my mother was healthy, able to live normally like the rest of us. I never really experienced a mother’s constant care—she herself needed looking after.”

Swarup’s health remained frail, and she endured prolonged periods of severe illness. Her sister Rajvati, widowed young, eventually moved to Allahabad to support her ailing sibling and manage the household.

Swarup’s role in the political sphere and her later years will be explored in our next blog.

Sources

Nanda, BR. The Nehrus: Motilal and Jawaharlal

Nehru, Jawaharlal. An Autobiography

Tharoor, Shashi. Nehru: A Biography